Advertisement

As cultural icons go, Jimmy Buffett was a slippery trickster. He was one of the great mystical troubadours of our lifetime. (Ask Bob Dylan). He was a middle-aged jester prancing before hordes of sunburned suburbanites, garishly dressed, making shark shapes with their hands. He was an authentic artist who mixed existing cultural elements in entirely fresh ways. He was a shameless shill in a shameless age. He was a rags-to-riches entrepreneur whose example spawned stirring tales of American enterprise. He was and was not an A-list pop star, whose diverse factions of devoted fans could be as different from each other as night is to day.

Jimmy Buffett was all these things. He was also a sailor, surfer, and fisherman who brought an enriching life on the water into our ears, into our hearts, and into our souls like nobody else on the public stage. He made people happy and made them dream. As we remember the singer/songwriter who died from Merkel cell carcinoma on September 1, 2023, let’s look back on Buffett’s magnificent life through the lens of four boats that reflected and shaped it.

Boston Whaler 13

In February 1974, ABC/Dunhill Records released “Living and Dying in ¾ Time” to modest sales. Nothing in the song titles hinted that this was something new under the sun, the early inklings of a pioneering musical genre. The writer Jim Harrison, much later, would dub it “Gulf & Western.” Today, under the umbrella of the Trop Rock Music Association (troprock.org), dozens of internet radio stations promote hundreds of working musicians. In this world, Buffett’s mid-1970s work was the Big Bang.

The buds of this new genre were apparent in the 1974 album but hadn’t yet flowered. Listen to the album’s fourth song. The title alone offers no clue; “Brahma Fear” merely evokes the timeworn cowboy component of a straight-up country and western number. Yet the lyrics in the second verse tell a different story: “Yes, I own a Whaler boat. It slides across the sea. Some folks say I’m part of it, and I know it’s part of me.” Where did the creator of this genre come from, and how did he find himself in such a deeply consequential Boston Whaler 13?

James William Buffett was born in Pascagoula, Mississippi, on Christmas Day 1946 and raised in Mobile, Alabama, by serious parents who sent him to Catholic schools, expecting him to become a U.S. Navy officer, or at least a good Southern lawyer. Instead, he washed out of Auburn University, banked some credits at Mississippi’s Pearl River Junior College, and ultimately graduated in 1969 from the University of Southern Mississippi with indifferent marks.

At Auburn, the freshman naïf, still more Catholic altar boy than experienced co-ed, watched a Sigma Pi fraternity brother attract girls with his guitar. Johnny Youngblood agreed to teach Jimmy three simple chords – G-major, C-major, and D-major – and the young acolyte practiced those with all the energy he never put into his Auburn classes.

From Pearl River Junior College it’s only 75 miles down US 11 to Bourbon Street in New Orleans. Buffett played covers at open mics. With several college friends he formed The Upstairs Alliance out of a second-story French Quarter apartment on Ursulines Street. A part-time shipyard job qualified him for credit to buy a sound system at a Mobile music store – his PA, his band. He wasn’t yet 20.

By 1970, a recently married Buffett had moved to Nashville with his new wife, hoping to break into the music business. Very quickly both Nashville and the marriage wore thin.

“Jerry Jeff Walker came to town,” Buffett recalled, “and a friend who worked at ASCAP was hosting him. We went out to the bar that night, and Jerry Jeff wound up at my house.” Soon after, a recently unmarried Buffett followed his hero to Miami looking for work.

“Jerry Jeff was the real deal, and there were all these other people coming through town – David Crosby, Rick Danko, Joni Mitchell. As a nobody, I couldn’t get over my luck, meeting all these people.”

In November 1971 Jerry Jeff proposed a road trip from Miami down the Overseas Highway, and Jimmy Buffett’s arrival in Key West was like a chemical reaction: Neither the man nor the place would ever be the same. Key West in those days had writers but didn’t yet have musicians or tourists – or, for that matter, margaritas. Ernest Hemingway was a ghost, while writers Jim Harrison and Thomas McGuane were alive and well and drinking at Capt. Tony’s Saloon. Truman Capote still turned up at Tennessee Williams’ infamous pool parties.

Buffett had found him a home – and stayed. The people he met and their exploits in those first few Key West years inspired “White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean” (June 1973). One track extols the pleasures of “sailing in those warm December breezes;” another, the “old red bike” that gets him around to the bars and beaches of his town.

It was those songs that bought him his first boat. A Key West banker had refused Buffett’s request for a $500 loan to buy the boat of his dreams, a Boston Whaler 13. But the $11,000 deal for “White Sport Coat” clinched it. In ABC’s video for Buffett’s first hit – or, as he later quipped about his entire life’s work, “one of my 2.4 hit records” – the man behind the wheel of a boat in the video for “Come Monday” could not possibly look happier in his newfound home on the water.

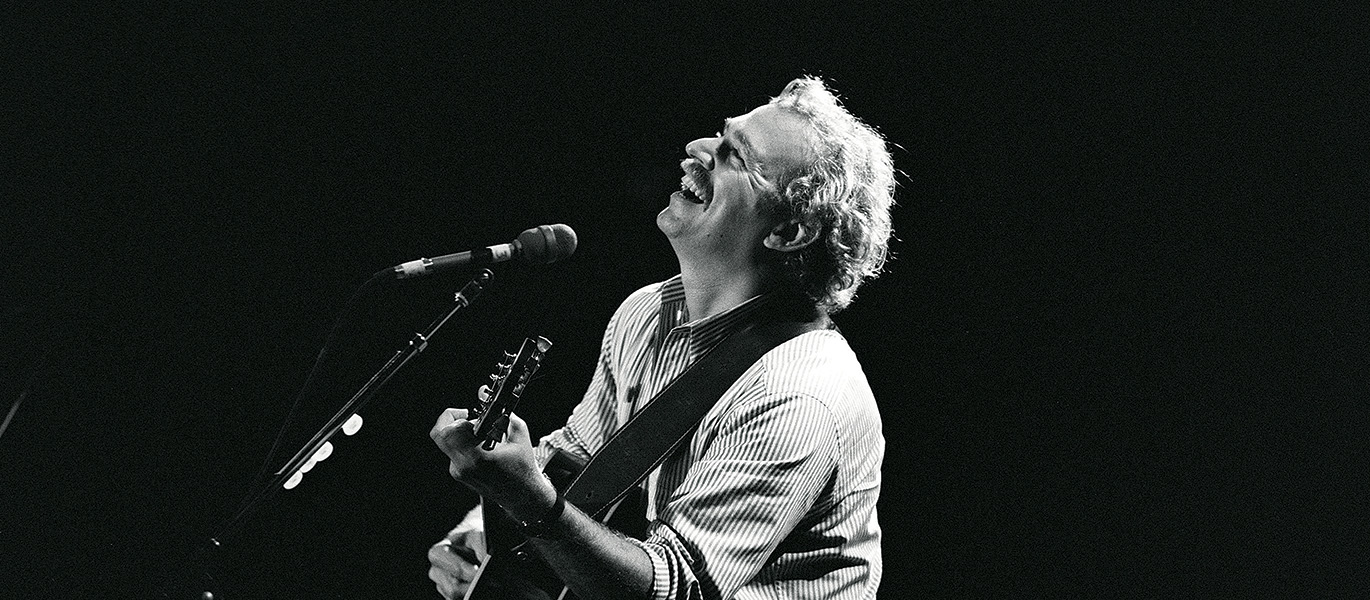

By the mid-1980s “Margaritaville” had become a brand and “Parrot Heads” had formed the phlock that never stopped growing. Photo: Kenneth Hagemeyer/CC BY-ND 2.0

Euphoria

If Jimmy Buffett’s pleasure with the Boston Whaler ran deep, writer/photographer Tom Corcoran’s camera caught something deeper still on October 18, 1976. It was the moment at Flagler Marina in Palm Beach, Florida, just after a yacht broker handed Buffett the keys to his first real cruising sailboat: a ketch-rigged Cheoy Lee 33. The photo’s subject wears a lime-green T-shirt from the Euphoria Tavern in Portland, Oregon. “There was a look of contentment like no one had ever seen before,” Buffett wrote of that photo in Tales from Margaritaville in 1989. More than a mere lark, he saw the sailboat as a personal connection to his sailing-captain grandfather and as a tangible insurance policy against the unsteady line of work he’d been plying for more than half a decade.

While “Come Monday” reached No. 30 on the Billboard charts, subsequent releases sputtered. Starved for paying gigs near his Key West home, Buffett traveled regularly to play shows around the country, frequently in Texas. He was on the bill for Willie Nelson’s 1974 Fourth of July Picnic at the Texas World Speedway that so famously went off the rails into mayhem and car fires. (For full-color detail, listen to the “No. 2 Live Dinner” version of Robert Earl Keen’s “The Road Goes on Forever.”)

Meanwhile, the life and characters of Key West inspired a new palette in the developing songwriter. For Buffett’s alt-country mentors, the outlaw was a fertile character type that filled an infinite well of songs from Willie Nelson, Townes Van Zandt, Johnny Cash, Merle Haggard, and others. As a boy, Buffett had been steeped in Jim Hawkins’ “Treasure Island” stories. And in his New Orleans days, the pirate Jean Lafitte haunted the Old Absinthe House, still up there plotting with Andrew Jackson to beat back the British fleet. Buffett’s songwriting leap from Texas outlaws to salt-stained pirates wasn’t so broad.

His Key West bartender friend, Phil Clark, was the real pirate.

“You just knew it,” Jerry Jeff Walker recalled in 1992. “He had that kind of breath, and those eyes.”

Clark really did run his share of grass, and really did sail off to places like Providenciales, returning with what must have seemed like enough money to buy Miami. When Buffett sang about Clark in “A Pirate Looks At 40,” he employed an old songwriter’s trick, swapping the third-person pronoun for the first. “Mother, mother ocean, I have heard you call.”

Who is this I? Phil Clark? Buffett? (Did Johnny Cash really shoot a man in Reno?) To the very end of his life, and beyond, Jimmy Buffett would be described as a pirate – an ambiguity the emerging performer cultivated from his earliest days in Key West.

Jimmy, right, tries his hand at the helm of the U.S. Naval Academy training sailboat Summerwind alongside skipper James Maitland in Annapolis, Maryland, in 2016. Photo: U.S. Navy/Alamy stock photo

But, oh, those songs. “Mother, mother ocean, I have heard you call. Wanted to sail upon your waters, since I was three feet tall. You’ve seen it all.” The incantation works like a prayer, finding its way straight to a boater’s heart. Lines like these made Buffett the undisputed bard of a new state of mind with its own particular approach to life. Through an alchemy that mixed sand, saltwater, bars, boats, cocktails, tire swings, and palm trees, Jimmy Buffett produced magic.

ABC/Dunhill saw something to back in these songs. A fall 1976 contract offered Buffett $132,000 to renew and another $100,000 to start work on the next record, three times the budget of his previous record, and 10 times that of his first. Producer Norbert Putnam, as disappointed as Buffett with Nashville, recommended a change of scenery for the next project: Criteria Recording Studios in Miami, Florida. At first Buffett balked. But then something dawned on him, and he wrote the song “Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes.” Buffett sailed Euphoria from Palm Beach to Miami, then spent two weeks of November 1976 making music history.

The recording project finished, he set off for the Bahamas aboard Euphoria with friends Tom Corcoran and Jane Slagsvol (who would later become his wife), National Lampoon managing editor P.J. O’Rourke, and 12-year-old Juan Thompson, son of gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson. Details from that trip appear in O’Rourke’s 1988 best-seller “Holidays in Hell.” The crew was halfway down the Exumas chain in Staniel Cay when Buffett stepped into a Batelco telecommunications building with one of the island’s only phones.

“That wasn’t supposed to be the single,” Corcoran heard him say. Euphoria quickly upped anchor and sailed off to Great Exuma, and Buffett embarked on a tour that never really ended for the rest of his days. “Margaritaville,” not “Changes in Latitudes,” was getting all the radio attention.

With “Margaritaville” money piling up, Buffett bought a larger Euphoria and set off to Tortola and St. Thomas, Caicos Islands, Dominican Republic, the eastern edge of the Bahamas, San Salvador, then 800 miles through the Atlantic to St. Maarten – on one passage with Glenn Frey of the Eagles. On the liner notes of his next album, Buffett wrote: “I have been a little too occupied changing winches, wiring spreader lights, repairing bilge pumps and numerous other jobs that go hand in hand with the pleasure of being a boat owner.”

Buffett takes his Tofinou 9.5, Groovy, for a sail in St. Barts. Above right: Promo photo taken aboard Euphoria. Photo: Shutterstock

Continental Drifter

Dan Streech, a lifelong sailor and cofounder of Pan Asian Enterprises, commissioned and distributed the iconic Mason 43 ocean-voyaging sailboat in 1980, then in 1988 the equally iconic Nordhavn 46 ocean-voyaging power yacht. At the news of Buffett’s death, Streech recalled his encounters with the singer.

“Every Nordhavn I’ve ever been aboard has had Jimmy Buffett music playing in the background,” he recalled. “When he sang about living lives of adventure, we believed he was singing about us. Then one day in 1998, he walked into our office and purchased N62 #2. He rechristened the boat Continental Drifter. I got to spend two fun days with Jimmy on board in Florida, two days I’ll never forget. That boat traveled many miles with, and for, Jimmy, and was seen up and down the Eastern Seaboard and the islands.”

Over the next several years, the Nordhavn would be replaced by two larger Continental Drifters: a Cheoy Lee Explorer 90, then, in 2003, the 124-foot Continental Drifter III built by Delta Marine in Seattle. The beach bum who failed the loan application for a Boston Whaler had become a mogul with a string of superyachts. The path from one to the other led through just one song.

Neither the producer nor its composer thought very much of “Margaritaville” during their November 1976 recording session in Miami.

“I wasn’t that excited about the title,” Putnam recalled. “A part of me sort of hoped he’d come up with a better song idea.”

The real-life scene that inspired it was at a Mexican restaurant in a strip mall near a freeway in Austin the previous spring. The songwriter had enjoyed several tequila drinks with a friend before catching a plane back home.

As Buffett told an audience in 2015, “She drove me to the plane, and I started the song. I got off the plane in Miami, and on the Overseas Highway there was a traffic accident on the Seven Mile Bridge. I sat there for an hour and a half, and I finished the song in three minutes.”

To everyone’s surprise, it cracked the Billboard Top 10, ultimately peaking at No. 8. By any ordinary music-industry standards, Jimmy Buffett would have been a one-hit wonder. But his life wasn’t ordinary, and neither was his career. While many diehard fans felt he took a wrong turn at “Cheeseburger in Paradise” (search “Church of Buffett, Orthodox”), something started building, slowly at first, almost invisibly through the early 1980s. By June 28, 1985, when Buffett headlined the sold-out Timberwolf Amphitheater near Cincinnati, he hadn’t had a radio hit in eight years. Timothy B. Schmit, formerly of the Eagles and Poco, was playing in Buffett’s Coral Reefer Band that summer. Looking out over a vast parking lot of wild revelers dressed in costume and bouncing colorful inflatable birds through the air, Schmit said, “These are your own personal Deadheads,” then corrected himself. “No, they’re Parrot Heads. You’ve got your Parrot Heads.” For a 30-year retrospective of this movement, the 2017 “Parrot Heads Documentary” on Netflix shows you everything you need to know.

After “Margaritaville” Buffett never had another Top 10 hit. That is, not until 2003 when Alan Jackson invited him to sing for 34 seconds on “It’s Five O’Clock Somewhere.” Still, through that decades-long “dry spell,” Jimmy Buffett did sell albums: in fact, nine platinum albums (more than 1 million sold), and eight gold albums (more than 500,000 sold). His 1985 compilation “Songs You Know By Heart” sold more than 7 million copies, and the “Boats, Beaches, Bars and Ballads” boxed set sold more than 4 million.

Buffett’s laid-back persona masked a shrewd businessman with an uncommon work ethic. In 1983 he noticed that the Chi-Chi’s restaurant chain touted every Tuesday as Margaritaville night: “Come, but be prepared not to waste away!” He sued for trademark violation and won. Partnerships began sprouting in 1984: Caribbean Soul T-shirts, a Margaritaville restaurant, the Margaritaville Store in Key West, founded on the mantra, as his partner Sunshine Smith recalled, “Don’t let your customers’ bad tastes get in the way of money.” By 2022 it was estimated that more than 20 million people pass through the doors of Margaritaville-branded businesses: casinos, hotels, restaurants, resorts, retirement communities. In 2023 Forbes magazine estimated Buffett’s net worth above $1 billion.

“’Margaritaville’ is a brand, a business empire, a point of view,” ran Life magazine’s summation in late 2023. “It’s perhaps the most profitable song in pop history, and the merchandizing that surrounds it – T-shirts, tequilas, tap rooms – has obscured its magic. First, and most important, ‘Margaritaville’ is a gorgeous song, life-loving and elegiac, finely crafted and cheeky, a nuanced nugget of genius."

Last Mango

Drop the needle on “Tin Cup Chalice,” the song that closes Buffett’s December 1974 album “A-1-A.” “I want to go back to the islands, where the shrimp boats tie up to the pilings. Give me oysters and beer for dinner every day of the year, and I’ll feel fine.” The song plays like a bohemian hymn: one man’s vision of heaven on earth, open to any who has ears to hear it or eyes to see it.

Three film clips, shot over some 50 years, stitch together an enduring expression of what that heaven might look like. In 1973 Christian Odasso and Guy de la Valdine produced “Tarpon” (tarpon1973.com), a 53-minute film in the cinema-vérité style that wasn’t commercially released at the time but that lived on in bootlegs and legend until 2008, when it was rescued from a barn and issued as a DVD. Jim Harrison, Tom McGuane, and Richard Brautigan (author of “Trout Fishing in America”) provided the onscreen talent. Jimmy Buffett wrote and performed the original film score.

Flats fishing, fly fishing, deep-sea fishing – through all the years of his life Buffett authentically pursued the moments he rhapsodized in his songs. In the 34-minute YouTube video “42’ Last Mango Walkthrough” (youtu.be/Dcavhrgpse0), his longtime captain, Vinnie LaSorsa, pulls back the curtain on Buffett’s last custom boat created for that mission: a 42-foot power catamaran built on a Freeman Boatworks hull, with a pilothouse designed and built by Merritt Boat & Engine Works, powered by quad Yamaha 300s. A boat that cruises at 40 mph and tops out at 60, Last Mango was built to cross quickly over to fish the Bahamas banks or to the Hudson Canyon. Buffett had put in 6,000 hours doing just that on the 15-year-old Rybovich-built Last Mango that the Freeman replaced.

“Yeah, now the sun goes sliding across the water. Sailboats, they go searching for the breeze. Salt air, it ain’t thin. It can stick right to your skin, and make you feel fine.”

“Tin Cup Chalice” is the song that plays through the background of a 2015 video clip made for Margaritaville TV (youtu.be/PYHoe4kzvs4). The segment captures Buffett, alone on Ballast Key before playing a Key West show later that night, fly-fishing the same flats he’d been returning to for decades.

“This is one of my favorite fishing spots,” he says. “In 1974 I think I came out here for the first time. Good tarpon, good bonefishing. As I’m walking around here today, I know that a couple of pretty good songs were written or inspired by events that went on out here on this island. Before we go out tonight to that show, it’s kind of neat to come out here and relive this a bit.”

“And I want to be there. I want to go back down and die beside the sea there, with a tin cup for a chalice. Fill it up, good red wine. And I’ll be chewing on a honeysuckle vine.”

Through his words and music, we can all relive it a bit.